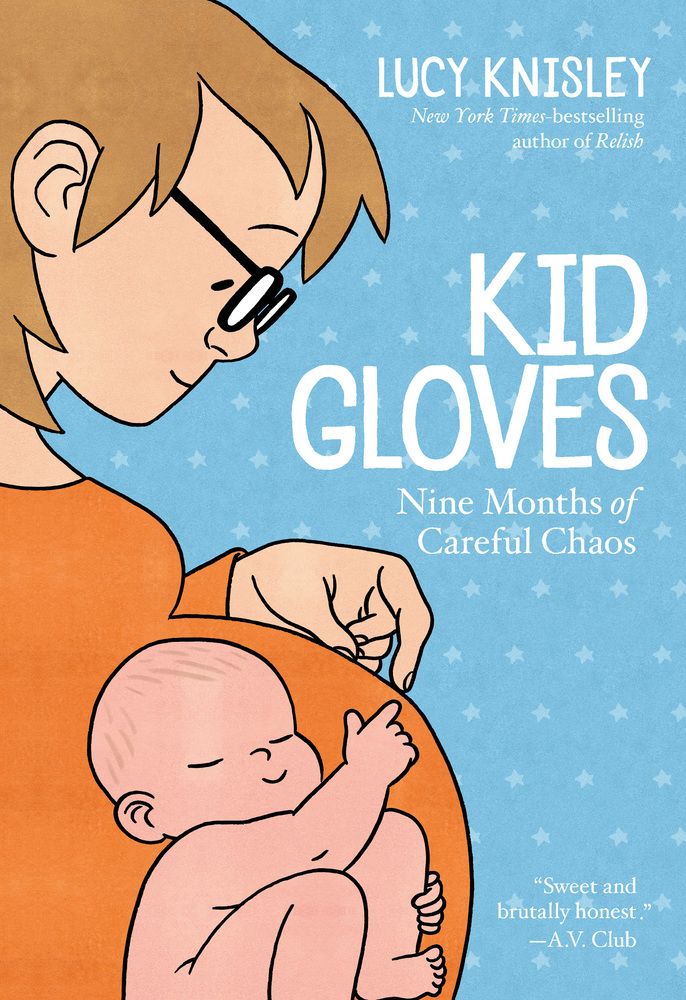

I had no baby shower, no celebrations, no companionship in the flesh as I navigated a first pregnancy that took years to achieve, thanks to infertility. There wasn’t a vaccine yet, and I never left home except to see my doctor. Pregnancy books in and of themselves were elaborate fantasy reads, filled with advice that was likely helpful in an era before masks, before lockdowns, before it wasn’t safe to just air out your feelings with fellow parents at a busy cafe. It felt like an unbelievable blessing to have my husband come with me to give birth and to be able to do so without needing to wear a mask, since he’d been vaccinated in time and I’d tested negative the day before my scheduled induction. My induction began on a Sunday morning, with the warning that it could take some time and not to necessarily prepare to have a baby soon. But Sunday turned to Monday turned to Tuesday turned to Tuesday night with a nurse who was said to have the “magic touch,” and indeed, her labor methods were helpful and different, but when Wednesday morning rolled around and nothing had worked to get the baby to drop, it was time for a cesarean section. No big deal for me, in part because I was so drugged up after two epidurals (the first one failed) and numerous blown IVs that led to an ICU nurse coming in with the anesthesia department to find a place for a midline catheter. I do not remember much of those days. I remember being on oxygen for a bit, as well as asking the anesthesiologist’s partner her name — she shared it with my to-be-born baby — and asking, after the spinal block, whether or not I could “let go of my body” (yes, please, please do, said the anesthesiologist). I was told to prepare for a blood transfusion, since I developed anemia around week 33 of the pregnancy, but otherwise, since this was now a scheduled, as opposed to emergency, c-section, all should be fine. And it was. But 24 hours or so after the c-section, somewhere in the bleary early morning hours, one of the postpartum nurses shocked me out of my “just had a baby” haze. My blood pressure was high enough that I was close to having a seizure with potentially deadly consequences and I’d need to be transferred back to maternity. What transpired in the transfer could be best described as anger, frustration, and feeling deeply loved and cared about. Despite COVID, another nurse asked if she could give me a big hug because after four days of labor, now being diagnosed with postpartum preeclampsia was a horrible lot. Preeclampsia shows up a lot in literature by and about pregnant people. This is when the body, without any underlying reason, sees sharp increases in blood pressure. It can quickly lead to eclampsia, better known as having a stroke. The way that preeclampsia is handled is pretty straightforward, though not without potential complication: you deliver the baby. My blood pressure stayed below the threshold for preeclampsia, though a couple of days before my scheduled induction, I checked myself into triage, since I was feeling many of the symptoms — I was checked and discharged after a nap in the room helped lower my blood pressure. Postpartum preeclampsia, however, is not so cut and dry. They start with one tactic and move through numerous others, including a magnesium drip (brutal), a wide range of medications (some which helped and some which didn’t), and so much fluid. I couldn’t get out of bed to do as much as use the bathroom, and attempting to breastfeed became a herculean task while wound in numerous medical tubes and fighting the dizzying, exhausting side effects of the magnesium. One night, I told the lactation consultant that as much as I appreciated her and her help, she needed to leave because I could not keep my head up. I went in and out of conscious awareness for three and a half days, and my awesome nurses, who were sad to keep stressing me out with the constant beeps of the blood pressure monitor’s “warning” indicator, finally turned the sound all the way off. I could not get out of my bed, could not shower or bathe because of the exhaustion and the midline catheter (the nurses were amazing in helping me to at least brush my teeth with a cup of water), could not hold or feed my baby. I cried between those things and the reality of also trying to recover from major surgery. On day two of treatment, I was mad. My doctor had told me preeclampsia could happen up to six weeks postpartum, so this wasn’t a surprise that it happened. As much as I didn’t think it would happen to me, it did, so that wasn’t the source of my anger. Rather, my anger came because I had never once read about postpartum preeclampsia in a book about what to expect in pregnancy. People asked why we weren’t home yet from the hospital. People asked what was wrong or what they might be able to do to help out. My mom and my friend went from caring for our pets for a couple of days to doing so for a week — and noticing how even our pets were growing anxious in our absence. The only way I could answer them and assure them what was going on wasn’t out of left field, wasn’t a result of any choices I’d made or anything that had happened with the baby, was through a single article in The New York Times, aptly titled “I Could Have Died“: There is indeed little research on postpartum preeclampsia, but it’s not an uncommon outcome for pregnant people. The story within the Times article suggests the numbers may be far higher than we know them to be, and more, it’s preeclampsia which can lead to maternal mortality rates — and though the piece doesn’t delve in, it’s not hard to imagine that that goes even more for pregnant folks who aren’t cis and white or middle-to-upper class. And yet, it’s an absent phenomenon in literature altogether. Too often, the challenges of pregnancy shared in books are those which come before baby, much like obstetric care itself. It’s assumed once baby is out of the host body, the birthing person no longer needs adequate care (indeed, when I talk about my experience with postpartum preeclampsia, I not only use the “I almost died” language, but I also note that because I almost died, I was able to access two additional OB appointments before the standard six-week check). I’ve been unpacking the trauma of this since my baby’s birth. In late 2019, I blew through Lucy Knisley’s Kid Gloves. She’s around my age, lives not far from me, and has always written comics that I find a lot of comfort in, as well as relate to in ways that are unexpected. It was in Kid Gloves where I first learned about the history of pregnancy and obstetrics, as well as better understood what people meant by the idea of “natural birth.” Knisley went down a ton of rabbit holes during her struggles with achieving viable pregnancy, and her research is included in digestible portions throughout the comic. As I read the comic, I was angry. I realized — like she does herself — how few stories of pregnancy focus on the mother and her experiences and needs. But more, Knisley’s book landed in my hands right when I’d had my first miscarriage. There’s so little education and talk about what bodies do or don’t do. Those who can give birth are under the impression it’s easy. It’s not. I know so few who have had easy, uncomplicated pregnancies (let alone births). I didn’t know about the ways a body doesn’t create the fetus “like it should” until I experienced that myself. Seeing it on the page there, her second miscarriage, really knocked the breath out of me, since that was my experience of a few days of potential only to learn that nothing ever happened. There’s a panel in the comic where Knisley’s birth plan is a single line: “bring home a healthy baby.” Whether it was intentional or not, that idea embedded in my brain, and when I found myself in the late weeks of my pregnancy two years later, I kept asking my doctor if it was okay I had no plan. “It’s anecdotal,” my doctor said, “but I’ve seen parents who don’t have an elaborate plan are the ones with the happiest outcomes.” I took it to heart and walked in with two items on my plan. The first was bringing home a healthy baby and the second was accepting all of the wonders of pain reduction offered by science. What I didn’t remember about Knisley’s comic, though — something that maybe my brain protected me from — was her own bout of postpartum preeclampsia turned eclampsia. I picked up Kid Gloves again recently and tore through it. I felt the same rush of anger the entire time I read it, but I also felt like I finally was having the much-needed conversation I’d needed during those lonely pandemic pregnancy months. It’s the conversation I needed now, with a healthy, happy, thriving baby even deeper into the pandemic. This read, I found myself in tears. Knisley had a stroke after her emergency c-section. She was admitted to intensive care, strapped and laced into machines, pumped full of medications to keep her body alive. Much of that period of time is loosely plotted in the book, with gaps in memory and experience more prominent than the actual happening. She talked of the struggle to hold her new child. She depicted the misery of being out of body in a way that’s beyond the “typical” out of body experiences for new parents. She illustrated the physical, mental, and emotional drain of a magnesium drip. The inability to ask for help, to be awake and alert to new life, the struggles to breastfeed, to not feel like a burden to a partner who is navigating a sick wife and a brand new child, to not recount every sign of what was to come that felt so obvious — extremely swollen feet, higher-than-average blood pressure, unrelenting thirst, a brutally long labor. I felt closer to her than I’d ever felt to another human being in ages. Knisley’s experience was far more excruciating than mine. Her doctor waved off all of her symptoms as no big deal, as routine impacts of pregnancy, especially for a first timer. She had a stroke, and even when she was discharged, she knew things weren’t better, and she was readmitted a day later. Even in her haze, the best word to describe the experience, she knew things weren’t OKAY much as she wished they were, and that her doctor’s negligence contributed to her lengthy physical pain. I, too, remember crying and begging to go home from any nurse who came in, and I knew, too, I was too sick for that to happen (I had the luxury of insurance coverage that Lucy did not, but I spent one night in my magnesium haze panicking about how many tens of thousands of dollars this would cost — I should have wondered in hundreds of thousands). Like me, Lucy turned to books and didn’t see what could happen to her. She learned history, she learned about birth plans and best baby cribs, found manuals for how to successfully breastfeed. This time when I closed it, I pressed the book to my chest like I do my child. All of the emotions I’d felt the first time around were amplified, but more, I felt a wave of gratitude I hadn’t in ages. My experience, laid bare on the page, allowed me to process even more of the pieces of trauma that have slowly edged their way into my mind daily. Knisley wrote this book to document her life, but — and she says this herself — she wrote it for me. She wrote it for me, as well as the thousands of other new parents who don’t have the full story or the full range of possibilities of what could happen shared with them. Too often, pregnancy is the before and the after. There’s not enough of the during, not enough of the realities of what happens to the pregnant person, and not the fetus they’re carrying. Culturally, it’s uncomfortable. Pregnant people are but vessels, as evidenced by the decades-long debates about abortion. (I, like so many others, have become even more fiercely pro-abortion following my experiences: they should be made available to anyone, at any time, for any reason.) But pregnant people are people in and of ourselves. We have lives, dreams, and hopes for ourselves beyond our offspring. We deserve to be the center of the story and not on the periphery of it. It’s vital we know the full story of what could happen, so that we can prepare. So that we can advocate for ourselves and for others. So that we don’t feel we must accept a doctor’s negligence and laziness when it’s easier to just sign off on a discharge, rather than listen to a patient saying something isn’t right. I learned when I was discharged a full week after being admitted to the hospital that the system was part of a major project in my state documenting and treating postpartum preeclampsia. The discharge nurse told me that in the few days of the month where I was being treated, they’d had more postpartum preeclampsia cases than they had the entirety of the month prior. I was one of the few who didn’t get discharged and need to come back. More research into postpartum preeclampsia is suggesting it’s possible to have symptoms crop up beyond the six-week window. But it’s taken incredible effort on the part of healthcare workers and their patients to have this serious illness be seen as such to begin with. It remains to be seen what the pandemic’s impact is on the understanding of postpartum preeclampsia, too — the body keeps the score, and as our bodies continue to tick onward through a global health crisis and all of its ramifications, it’s not a stretch to connect an increase in postpartum emergencies with an increase in non-stop exterior stress. As I stumble through this first year of my child’s life, angry and sad, joyful and grateful, I’m finding bits and pieces of those lost hours and days coming back, though I know much is lost forever. That’s my brain protecting me. All I can hope for is stories like mine, which I share as openly and frankly as possible, can leave another person feeling like I did in reading Knisley’s. Kid Gloves is the book I’ll be giving and recommending to new parents for the rest of my life.