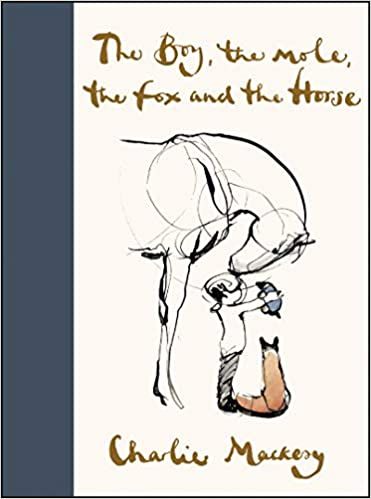

On the surface, The Boy, the Mole, the Fox and the Horse by debut author Charles Mackesy seems to be an especially unlikely fit for this kind of success. It’s a 128-page book of unsophisticated drawings and seemingly disconnected messages. It has no real plot, just a collection of misfits coming together, quietly expressing their vulnerabilities, and quietly accepting each other as well as the struggles of their journey to an unknown destination. That’s it. There’s a tea cup stain, it doesn’t even rhyme, and it’s become an international phenomenon. It’s impossible to know for sure how such a thing happened. But the story of one copy of that book might shed a little light on the matter. When a friend sent me a copy last December, I’d only heard of it in passing — probably in a conversation about sales or bestsellers. I didn’t think much of it, since a book of daily horoscope-style messages about friendship, love, acceptance, and patience isn’t normally my kind of book. But the friend who sent it did so because I had suddenly and completely lost my hold on “normal.” In December of last year, my sister died unexpectedly following a relatively low-risk surgery. In addition to being a sister, spouse, and daughter, she was also a parent of two children who were, at that time, 18 months and 3 years old. Experiencing the grief and uncertainty that descended on our family in the immediate aftermath felt like slipping into quicksand — quiet, lonely, and slowly but surely all-consuming. For me, there was almost nothing that could break through that kind of grief. I guess there’s probably a podcast or meditation app or a Brené Brown book for that, but my brain was so full of “what the actual fuck are we going to do?” that there wasn’t space for those things. As it turned out, one of the only things that could sneak through the cracks in a wall of loss were the short, scribbly messages in The Boy, the Mole, the Fox, and the Horse: “’What’s that over there?’ ‘It’s the wild,’ said the mole. ‘Don’t fear it.’” “This storm will pass.” “Just take this step…The horizon will look after itself.” I can understand how passages like those might seem a little trite. When I reread the book now, nearly a year later, I see how many readers might take the messages in this book as platitudes. But following my sister’s death, these kinds of short, straightforward sentences made more sense than anything else, since at that point, all of the communication in our family was brief: “The obituary is running on Sunday.” “I’ll rock him back in the bedroom for a while to see if I can get him to take a nap.” “The church needs our list of emails and phone numbers for contact tracing by Friday.” “I called the child care center and the pediatrician. Who’s next on the list?” “She can’t come back. But she still loves you very, very much.” It turns out you only need a handful of words when there’s almost nothing to say. The Boy, the Mole, the Fox and the Horse was well-received upon its release in October 2019, selling 250,000 in the United States by January 2020. It’s reasonable to wonder, though, if some if its ongoing connection with readers is related to the fact that so many people have had to navigate tragedy and grief over the last two years. In additional to individual tragedies like the one that struck my family, national and international crises have had personal impacts for so many, and I’m certainly not the only person who has come to this book through loss. Mackesy explains in the introduction of his book that the characters’ adventures “happen in the springtime where one moment snow is falling and the sun shines the next, which is also a little bit like life — it can turn on a sixpence.” It’s hard to think of a time when that has been so true for so many people. Short, easy to process text and timing alone likely wouldn’t have been enough to drive the devoted following Mackesy’s book has obtained — or at least, it wouldn’t have been enough for me. There’s also something about the feel of this book and specifically the kindness and empathy that ground it. Lots of readers probably have a favorite page or passage in The Boy, the Mole, the Fox and the Horse, but I think the most important page in terms of the connective power of the book is one that reads: “’The greatest illusion,’ said the mole, ‘is that life should be perfect.’” It’s not the text you notice first; unlike the other pages, this one has ink smudges and water droplet marks over the picture of the boy and the mole in a tree, and Mackesy explains the messiness and imperfections in a small pencil note at the bottom of the page: “My dog walked over the drawing — clearly trying to make the point.” Mackesy could have re-done the page, but he didn’t, instead leaving the flaws and letting them and his note explaining them break the fourth wall and bringing us inside the book, inside the story, inside its little cast of creatures. The smudges are a reminder that this book is not some kind of transcendent or otherworldly text. It’s a book by a human artist who has a dog and is sharing some basic reminders about love and struggle and connection and cake. No part of the book is intimidating, but that page feels especially accessible, even a little bit conspiratorial. After all, if Charlie Mackesy is willing to acknowledge and celebrate accidental ink smudges, maybe we really are all on this strange journey together. The Boy, the Mole, the Fox and the Horse isn’t magic. It won’t replace counseling or therapy. It’s not a long-term solution to dealing with loss or grief, and I don’t believe Charlie Mackesy meant it to be any of those things. I think this book is instead offering permission to pause and to grant yourself some grace and compassion. It’s a simple reminder that love survives even the darkest days. It’s a hard copy illustration showing that no storm lasts forever, and that no matter what else is true, we still live in a world with cake. At least that’s what it was for me. And judging by the numbers, I’m not the only one who’s needed it.